From the colonial period to the recent battles in Congress, indigenous rights are under constant threat

By Alicia Bastos*

Brazil celebrates the Indigenous Day on 19 April since 1943, when the commemorative day was created by President Getúlio Vargas – in memory of the day (April 19) in which several indigenous leaders of the Americas decided to participate in the first Inter-American Indigenous Congress, held in Mexico in 1940. Since then, this day call us to reflect on the importance of cultural values of indigenous peoples and the repesct to their rights.

To better understand their position let’s begin from the times of the peaceful life of indigenous people in Brazil, when they lived in harmony within the jungle and their people, across the Brazilian coast and the banks of rivers.

After colonisation around 1550’s, Indians were seen as wild and dangerous, being soon slaved by the Portuguese to work on sugar cane plantations. Being hard to capture and fragile to diseases brought by Europeans, thousands of indians and their people were killed with tuberculosis, smallpox, influenza and other viruses.

In 1570, King Sebastian I, ordered Indians to be free from slavery but was not only until 1755 they were abolished.

By the middle of 16th century the Jesuit priests worked to covert them to Catholicism, creating the Missions, little villages filled with what they called ‘civilised indians’, and but by the mid 1770’s, the Jesuits were expelled

from Brazil and all those villages were emptied and sold. The indigenous people kept been attacked or ‘purposely infected’ with smallpox by being given infected clothes by villagers that wanted to expand their cattle creations over indian tribe’s lands in regions like Maranhão, in the north east of the country.

When the rubber boom happened in the Amazon around 1840, several peasants were brought to the Amazon to work, because Indians resisted working and were target as bad workers. The growing presence of peasants brought conflict with the indigenous peoples and more diseases.

During the same period, Marshall Cândido Rondon, a Portuguese and Bororo indian mixed race army officer, were visiting Amazon to install telegraphs and ended up seeing the way indigenous people were being treated and decided to create the Serviço de Proteção aos Índios – SPI (Service for the Protection of Indians). Rondon’s commitment with the indigenous died with in in 1958 and the organisation tried in fact to force indian people into mainstream society.

In the beginning of the 60’s three brothers of the Villas-Boas family, who were activists and worked with Indians for many years, made a huge effort and succeeded to create the first indigenous protected area, the upper Xingu River and following it, others were created. They were also bringing into public eyes denounces of atrocities towards indigenous people. Xingu, directed by Cao Hamburger, portrays the mission of the Villas Boas.

In 1967, the Figueiredo report, exposed 5000 pages in histories of sexual abuse, slave work, violence, torture and collective murder, proving SPI to be a corrupt organisation, partially responsible for over 80 tribes to disappear and responsible for much of the criminalities against the indigenous..

After the report, SPI became FUNAI, the National Indian Foundation of Brazil, a governmental body to protect Indians and today responsible for maintaining policies about indigenous in Brazil and protect their rights following the constitution and the Indian Statute. Their work includes mapping the indigenous peoples and their lands, and prevent their invasion by explorers of natural resources.

But it is important to highlight that when FUNAI was created there was nothing but a heavy heritage from SPI as a failed organisation in terms of their relationship with the indigenous peoples. In 1967, Brazil was under military power, and with it there was a progressive political programme, to expand and explore the Amazonian territory. During that period, with money from the World Bank, large areas of the forest were made into cattle farms, the Trans-Amazonian highway was being constructed, hydroelectric dams were being created, and more migrants were coming as working force. All this development has not only contributed to a beginning to a continuous destruction of the environment but it has directly affected hundreds of indigenous tribes, their land and their water.

In 73, the law 6 001, or the Indian Statute comes into place, following the Brazilian Civil Code of 1916 with the Indigenous being protected under a state agency.

In the re-democratisation of the country by the 80’s after military power, the indigenous movements gained voice but it wasn’t until 1988 with the new constitution from the young democracy, the indigenous rights to their traditional lands were officially protected. From that moment, FUNAI had the constitution to follow and it was to assist with their needs but also had as a responsibility to support on their lands protection and demarcation.

Since then, the indigenous people have been demanding a revision of their statute, considering the fundamental change of legal status, form before the constitution being under legal protection of the state agency FUNAI and then being independent. The revision was advanced in 1992 and since 1994 has not been taken in consideration.

LAND ISSUES

The land issue is an endless technical fight to demarcate their lands and has been evolving slowly, stuck in the land reforms propositions, against political and national and international businesses interests, with the lack of heavy legal support, either indigenous groups or FUNAI have been able to finalise this process. In 2013, from the 1.46 demarcated lands, only 363 are regulated.

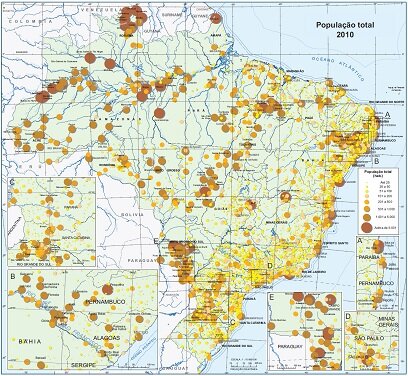

In Brazil 12% of the land belong to indigenous people. From these, 90% are in the Amazon.

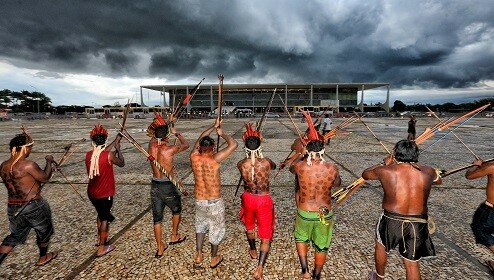

In 2000 a Proposed Constitutional Amendment (PEC) 215 intended to give the Legislature the rights to approve and formalise Indigenous Lands, Units of Conservation (UCs) and Quilombola Territories. However, this power already belongs to the Executive, so what it proposes in unconstitutional. This amendment was created with the support from Agro-business interests and since then, the amendment voting has been stopped a few times, revised and it was only in December 2014 that it was demanded to be archived once it was as not approved. 1,500 Indigenous Peoples came from all Brazil occupying the Esplanade of Ministries in Brasília to fight for their rights.

On the second Lula mandate in 2007, the Programme of Acceleration and Growth (PAC, Programa de Aceleração e Crescimento) was created, “promoting the planning and execution of great works of social infrastructure, urban, logistics and energy of the country, contributing to its accelerated and sustainable development.” – as we can read on the government website.

And the PEC 215 is only one of the following Proposed Amendments to the Constitution (PECs) numbers 038/99, 215/00 and 237/13, Bill 1610/96, the bill for Complementary Law (PLP) 227/12, and the Portarias (ministerial orders) 419/11 and 7957/13, that are legal initiatives that prioritise the development of agribusiness and mining over indigenous lands:

- PEC 38 proposes giving the Senate power to approve processes of demarcation of Indigenous lands, determining that “the demarcation of Indigenous lands or units of environmental conservation respect the maximum limit of 30% of the surface area of each state”;

- PEC 237 permits the possession of Indigenous lands by rural producers;

- PLP 227 deals with regulations to Article 6 of the Constitution, in relation to exceptions to the exclusive use of the Indigenous Peoples to their lands at federal level;

- Portaria 419 intends to streamline the licensing of public projects by means of the reduction of Indigenous rights, of the rights of traditional communities and of the environment;

- Portaria 7957 creates the Environmental Operations Company of the National Force of Public Security to permit the use of military force against Indigenous Peoples who oppose the large-scale projects of the PAC (Program for Acceleration of Growth), especially hydroelectric dams;

- PL 1610, allows mining in Indigenous lands.

CURRENT DAYS

FUNAI has gone through a rollercoaster, trying to gain the indigenous trust, deal with the government interests, and fighting to keep their integrity within a corruptive culture and budget cuts that considerably reduces its worker numbers, resulting in today almost half of the employees are senior workers that are about to retire.

The former president of FUNAI, Maria Augusta Assiratti comments honestly and openly about the challenges of the organisation in a talk organised in London in April 2015 by the Brazil Institute of King’s College and ABEP.

She said: “For one year leading the organisation, everyday it was necessary to state that our vision is different of the Brazilian current political unilateral development policies, those objectives are contrary of our truth as an organisation created to support and protect indigenous people, their culture and lands. Today FUNAI faces the same dilemma of 1967, to achieve our objectives, deal with the indigenous expectations and demands, but at the same time, go against the government decisions.”

On the same event, there were present Fiona Watson Survival International, two indigenous Nixiwaka Yawanawá and award winning film maker Takumã Kuikuru, academics and photographer Sue Cunningham that together with husband Patrick runs several projects in Xingu river from about 20 years now.

Although lands are their major issue, it is scientifically proven, by satellite images that indigenous people are the best guardians of our forest, their occupancy protects our lands from drastic consequences of logging, mining, oil interests and cattle farming. With that we include the development of dams in the Amazon, like the internationally known case of Belo Monte, which is only one of the many hydroelectric dams planned in the Amazon rivers.

The almost 900,000 indians in Brazil in 304 ethnic groups or tribes (Sensus IBGE, 2010) face extraordinary challenges to fight for their rights, from their geographical locations, their communication amongst themselves having and 274 languages (IBGE sensus 2010), their level of involvement with the mainstream society lifestyles. Another difficul issue is the trust in organisations and people that offer help and the struggle to find one way of help considering the diversity of the indigenous people and their issues urgencies. However, they are fighting, the indigenous population of Brazil is growing, is being studied, is gaining voice, and getting public opinion and support.

Nixiwaka Yawanawá said: “We are not going to disappear and whilst there is one indian standing, we will fight. Today, I use the knowledge of the ‘super white’ to be able to help my people”.

*Alicia Bastos is founder and artistic director of Braziliarty

Special screening of The Hyperwomen, followed by talk and drinks with indigenous film director Takumã Kuikuro at the Embassy of Brazil in London